Fredric Wertham

Fredric Wertham | |

|---|---|

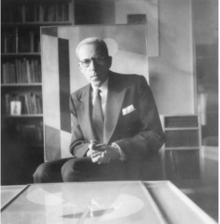

Wertham at his Gramercy Park office. Photo by Gordon Parks. | |

| Born | Friedrich Ignatz Wertheimer March 20, 1895 |

| Died | November 18, 1981 (aged 86) Kempton, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Education | King's College London University of Munich University of Erlangen University of Würzburg (M.D., 1921) |

| Occupation | Psychiatry |

| Spouse | Florence Hesketh (1902–1987) |

| Signature | |

Fredric Wertham (/ˈwɜːrðəm/;[1] born Friedrich Ignatz Wertheimer, March 20, 1895 – November 18, 1981) was a German–American psychiatrist and author. Wertham had an early reputation as a progressive psychiatrist who treated poor black patients at his Lafargue Clinic at a time of heightened discrimination in urban mental health practice. Wertham also authored a definitive textbook on the brain, and his institutional stressor findings were cited when courts overturned multiple segregation statutes, most notably in Brown v. Board of Education.

Despite this, Wertham remains best known for his concerns about the effects of violent imagery in mass media and the effects of comic books on the development of children.[2][3] His best-known book is Seduction of the Innocent (1954), which asserted that comic books caused youth to become delinquents. Besides Seduction of the Innocent, Wertham also wrote articles and testified before government inquiries into comic books, most notably as part of a U.S. Congressional inquiry into the comic book industry. Wertham's work, in addition to the 1954 comic book hearings, led to the creation of the Comics Code Authority, although later scholars cast doubt on his observations. Comic book art remained stagnant until the 1970s.

Early life

[edit]Wertham was born Friedrich Ignatz Wertheimer on March 20, 1895, in Nuremberg[4] to the middle-class Jewish family of Sigmund and Mathilde Wertheimer.[5] Ella Winter (originally Wertheimer) was a relative. He did not change his name legally to Fredric Wertham until 1927. He studied at King's College London, at the Universities of Munich and Erlangen, and graduated with an M.D. degree from the University of Würzburg in 1921. He was very much influenced by Dr. Emil Kraepelin, a professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Munich, and worked briefly at the Kraepelin Clinic in Munich in 1922. Kraepelin emphasized the effects of environment and social background on psychological development. Around this time Wertham corresponded and visited with Sigmund Freud, who influenced him in his choice of psychiatry as his specialty.

Career

[edit]In 1922, he accepted an invitation to come to the United States and work under Adolf Meyer at the Phipps Psychiatric Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.[6] He became a United States citizen and married the sculptor Florence Hesketh in 1927.[2] He moved to New York City in 1932 to accept a senior staff position at the Bellevue Mental Hygiene Clinic, the psychiatric clinic connected with the New York Court of General Sessions in which all convicted felons received a psychiatric examination that was used in court.[2] In 1935 he testified for the defense in the trial of cannibalistic child rapist and serial killer Albert Fish, declaring him insane.[7] In 1946, Wertham opened the Lafargue Clinic in the basement of St. Philip's Church in Harlem, a low-cost psychiatric clinic specializing in the treatment of Black teenagers. The clinic was financed by voluntary contributions.[8]

Seduction of the Innocent and Senate hearings

[edit]Seduction of the Innocent described overt or covert depictions of violence, sex, drug use, and other adult fare within "crime comics"—a term Wertham used to describe not only the popular gangster/murder-oriented titles of the time but also superhero and horror comics as well—and asserted, based largely on undocumented anecdotes, that reading this material encouraged similar behavior in children.

Comics, especially the crime/horror titles pioneered by EC Comics, were not lacking in gruesome images; Wertham reproduced these extensively, pointing out what he saw as recurring morbid themes such as "injury to the eye" (as depicted in Plastic Man creator Jack Cole's "Murder, Morphine and Me", which he illustrated and probably wrote for publisher Magazine Village's True Crime Comics No. 2 (May 1947); it involved drug dealing protagonist Mary Kennedy nearly getting stabbed in the eye "by a junkie with a hypodermic needle" in her dream sequence[9]).

Many of his other conjectures, particularly about hidden sexual themes (e.g. images of female nudity concealed in drawings of muscles and tree bark, or Batman and Robin as gay lovers), were met with skepticism from his fellow mental health professionals, but found an audience in those concerned with "public morals", such as Senator Estes Kefauver, who had Wertham testify before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, which he led.[10][11]

In extensive testimony before the committee, Wertham restated arguments from his book and pointed to comics as a major cause of juvenile crime. Beaty notes "Wertham repeated his call ... [for] national legislation based on the public health ideal that would prohibit the circulation and display of comic books to children under the age of fifteen."[6]: 157 The committee's questioning of their next witness, EC publisher William Gaines, focused on violent scenes of the type Wertham had decried. Though the committee's final report did not blame comics for crime, it recommended that the comics industry tone down its content voluntarily; possibly taking this as a veiled threat of potential censorship, publishers developed the Comics Code Authority to censor their own content. The Code banned not only violent images but also entire words and concepts (e.g. "terror" and "zombies") and dictated that criminals must always be punished—thus destroying most EC-style titles, and leaving a sanitized subset of superhero comics as the chief remaining genre.

Citing one of Wertham's arguments, that 95% of children in reform school read comics proves that comics cause juvenile delinquency (an example of the well-known logical fallacy correlation implies causation), Stan Lee recounted that Wertham "said things that impressed the public, and it was like shouting fire in a theater, but there was little scientific validity to it. And yet because he had the name doctor people took what he said seriously, and it started a whole crusade against comics."[12]

Seduction of the Innocent also analyzed the advertisements that appeared in 1950s comic books and the commercial context in which these publications existed. Wertham objected to not only the violence in the stories but also the fact that air rifles and knives were advertised alongside them. Wertham claimed that retailers who did not want to sell material with which they were uncomfortable, such as horror comics, were essentially held to ransom by the distributors. According to Wertham, news vendors were told by the distributors that if they did not sell the objectionable comic books, they would not be allowed to sell any of the other publications being distributed.[citation needed] Also in 1954, Wertham was the Court's appointed psychiatric expert in the trial of the Brooklyn Thrill Killers. When the gang's 18-year-old leader admitted that he had read simply comic books, Wertham concluded that the books were to blame for his crimes.[13]

Later career

[edit]Wertham's views on mass media have largely overshadowed his broader concerns with violence and with overprotecting children from psychological harm. His writings about the effects of racial segregation were used as evidence in the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education, and part of his 1966 book A Sign for Cain dealt with the involvement of medical professionals in the Holocaust. To promote this book, Wertham made two memorable appearances on the Mike Douglas Show where he ended up debating his theories with the co-hosts, Barbara Feldon (April 10, 1967) and Vincent Price (June 19, 1967). Excerpts were shown at the 2003 San Diego Comic-Con.[14]

University of Calgary professor Bart Beaty, the only person allowed access to Wertham's personal papers before they were unsealed in 2010, reveals that Wertham tried in 1959 to sell a follow-up to Seduction of the Innocent concerning the effects of television on children, to be titled The War on Children.[15] Much to Wertham's frustration, no publishers were interested in publishing it.[16]

Wertham always denied that he favored censorship or had anything against comic books in principle, and in the 1970s he focused his interest on the benign aspects of the comic fandom subculture; in his last book, The World of Fanzines (1974), he concluded that fanzines were "a constructive and healthy exercise of creative drives". This led to an invitation for Wertham to address the New York Comic Art Convention. Still infamous to most comics fans of the time, Wertham encountered suspicion and heckling at the convention, and stopped writing about comics thereafter.[17]

Before retirement he became a professor of psychiatry at New York University, a senior psychiatrist in the New York City Department of Hospitals, and a psychiatrist and the director of the Mental Hygiene Clinic at the Bellevue Hospital Center.[2]

Death

[edit]Wertham died on November 18, 1981, at his retirement home in Kempton, Pennsylvania, at age 86.[2][18]

Accusations of falsified data

[edit]After Wertham's manuscript collection at the Library of Congress was unsealed in 2010, Carol Tilley, a University of Illinois librarian and information science professor, investigated his research and found his conclusions to be largely baseless. In a 2012 study, Tilley wrote "Wertham manipulated, overstated, compromised, and fabricated evidence—especially that evidence he attributed to personal clinical research with young people—for rhetorical gain."[19]

Among the criticisms leveled at Seduction of the Innocent are that Wertham used a non-representative sample of young people who were already mentally troubled, that he misrepresented stories from colleagues as being his own, and that Wertham manipulated statements from adolescents by deliberately neglecting some passages while rephrasing others such that they better suited his thesis.[10]

Legacy

[edit]Wertham's papers (including the manuscript to the unpublished The War on Children) were donated to the Library of Congress and are held by the Manuscript Division. They were made available for use by scholars for research on May 20, 2010.[20] A register of the papers has been prepared that displays the eclectic reach of Wertham's interests.[21]

In 2014, documentary filmmaker Robert A. Emmons Jr. produced the documentary Diagram for Delinquents, which details the complicated and controversial history of Fredric Wertham and comic books in the 1940s and 1950s.[22][better source needed] The film's goal was to create a more complex picture of Wertham than what had previously been depicted in comic book documentaries.[citation needed]

His activism was cited in the 2011 US supreme court decision Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association.[citation needed]

Wertham was satirized as a Dr. Bertham who was kidnapped and turned into a monster by a mad scientist in Seaboard's Brute No. 2 (April 1975).[23]

Issue No. 1 of Bongo Comics' Radioactive Man shows comics from a young boy's collection that satirize Wertham's negative view of comic books. These include Crime Does Pay (violence and gore); Headlights (women with ludicrously pointed breasts); Stab (pathological fixation on eye injuries); and Tales of Revolting Filth (pretty much subsuming every other category). Wertham himself is also parodied in the issue.[citation needed]

According to the supplementary material of the HBO series Watchmen, within that fictional universe Fredric Wertham created a system for cataloging the mental states of costumed adventurers.[citation needed]

The character of Doctor Fredreich "Werthers" on the last season of the CW show Riverdale is based on Wertham.[24]

Wertham makes an appearance in the fifth book of Dav Pilkey's Cat Kid Comic Club series in the short comic book I Am Dr. Fredric Wertham written by the character Melvin.[25]

Selected bibliography

[edit]- 1941: Dark Legend: A Study in Murder, Duell, Sloan and Pearce.

- 1948: "The Comics, Very Funny", Saturday Review of Literature, May 29, 1948, p. 6. (condensed version in Reader's Digest, August 1948, p. 15)

- 1953: "What Parents Don't Know About Comic Books". Ladies' Home Journal, Nov. 1953, p. 50.

- 1954: "Blueprints to Delinquency". Reader's Digest, May 1954, p. 24.

- 1954: Seduction of the Innocent. Amereon Ltd. ISBN 0-8488-1657-9

- 1955: "It's Still Murder". Saturday Review of Literature, April 9, 1955, p. 11.

- 1956: The Circle of Guilt. Rinehart & Company.

- 1968: A Sign for Cain: An Exploration of Human Violence. Hale. ISBN 0-7091-0232-1

- 1973: The World of Fanzines: A Special Form of Communication. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-0619-0

- 1973: "Doctor Wertham Strikes Back!" The Monster Times no. 22, May 1973, p. 6.

See also

[edit]- Comics Code Authority

- Jack Thompson (activist)

- Moral panic

- Motion Picture Production Code

- Parents Music Resource Center

- Terry Rakolta

References

[edit]- ^ "Introducing Wertham". SequartTV. December 14, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c d e Webster, Bayard (December 1, 1981). "Fredric Wertham, 86, Dies. Foe of Violent TV and Comics". New York Times. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Van Lente, Fred (2011). The Comic Book History of Comics. San Diego: IDW. pp. 79–80.

- ^ birth certificate at the archive of the city of Nuremberg, Stadtarchiv Nürnberg C 27/IV Standesamt, Geburtenregister Nr. 521, Eintrag Nr. 1302

- ^ "Wertham, Fredric (1895–1981)". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Beaty, Bart (2009). Fredric Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. p. 16. ISBN 978-1578068197.

- ^ "Fish Held Insane By Three Experts. Defense Alienists Say Budd Girl's Murderer Was And Is Mentally Irresponsible". The New York Times. May 21, 1935. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Springhall, John. Youth, Popular Culture and Moral Panics: Penny Gaffs to Gangsta-Rap, 1830–1996. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998.

- ^ Spiegelman, Art; Kidd, Chip (2001). Jack Cole and Plastic Man: Forms Stretched to their Limits. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books. p. 91. ASIN B013ROSW0U.

- ^ a b Itzkoff, Dave (February 19, 2013). "Scholar Finds Flaws in Work by Archenemy of Comics". The New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ Weldon, Glen (April 3, 2016). "A Brief History of Dick". Slate. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ Boatz, Darrel L. (December 1988). "Stan Lee". Comics Interview. No. 64. Fictioneer Books. p. 17.

- ^ The Incredible True Story of Joe Shuster's NIGHTS OF HORROR, Comic book legal defense, October 3, 2012

- ^ Blogging From the Con

- ^ The manuscript is in Box 149, folder 4 of The Papers of Fredric Wertham, 1818–1986, Library of Congress Rare Books and Special Collections Division.

- ^ Beaty, Bart (2009). Fredric Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. p.170-176.

- ^ "Biographies: Fredric Wertham, M.D." Comic Art & Graffix Gallery. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011.

- ^ "Death Revealed". Time magazine. December 14, 1981. Archived from the original on October 15, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Tilley, Carol (2012). "Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications that Helped Condemn Comics". Information & Culture. 47 (4): 383–413. doi:10.1353/lac.2012.0024. S2CID 144314181.

- ^ "Wertham's Locked Vault". Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Fredric Wertham: A Register of His Papers at the Library of Congress

- ^ Diagram for Delinquents

- ^ "The Brute #2". atlasarchives.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ^ Zalben, Alex (April 6, 2023). "Why 'Riverdale' Brought Back Murder Mysteries in the Final Season: "In the DNA" Of The Show". Decider. Retrieved December 1, 2023.

- ^ "3 Million Kids Will Learn of Dr Frederic Wertham Thanks to Dav Pilkey". bleedingcool.com. October 16, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- (1954). "Are Comics Horrible?" Newsweek, May 3, 1954, p. 60.

- Beaty, Bart. Fredric Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture. University Press of Mississippi, 2005. ISBN 1-57806-819-3

- Bowman, James. "In Defense of Snobbery". August 26, 2008. [1]

- Decker, Dwight. (1987). "The Strange Case of Dr. Wertham" Amazing Heroes No. 123 (August 15, 1987); "The Return of Dr. Wertham" Amazing Heroes No. 124 (September 1, 1987); "From Dr. Wertham With Love" Amazing Heroes No. 125 (September 15, 1987) [three part series, see below for a link to the condensed version posted online under the title "Fredric Wertham – Anti-Comics Crusader Who Turned Advocate"].

- Gibbs, Wolcott. (1954). "Keep Those Paws to Yourself, Space Rat!" The New Yorker, May 8, 1954.

- Hajdu, David. The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008. ISBN 0-374-18767-3

- Larson, Randall D. (1971). "An Interview with Fredric Wertham, M.D." Fandom Unlimited No. 1 (fanzine, 1971).

- Larson, Randall D. (1977). "Violence in Cinema: An Interview with Fredric Wertham, M.D." Fandom Unlimited #2 (fanzine, 1977)

- Amy Kiste Nyberg. "Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code". University Press of Mississippi, 1998. ISBN 0-87805-975-X

- Carol L. Tilley. (2012). Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications that Helped Condemn Comics. Information & Culture: A Journal of History. 47 (4), 383–413. DOI 10.1353/lac.2012.0024

External links

[edit]- Fredric Wertham – on Lambiek Comiclopedia

- Fredric Wertham – Anti-Comics Crusader Who Turned Advocate – condensed online version of Dwight Decker three-part series listed above

- The End of Seduction – lengthy history of Wertham and censorship of comics

- Comics Reporter: "Let's You and Him Fight" Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5 – Bart Beaty and Craig Fischer discuss Beaty's "Fredric Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture"

- No Evil Shall Escape My Sight: Frederic Wertham and the Anti-Comics Crusade – lecture by Dr. Chris Bishop, Australian National University, at The Library of Congress

- Wertham Collection: Publications primarily related to psychology at the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- 1895 births

- 1981 deaths

- 20th-century German Jews

- 20th-century American physicians

- 20th-century German physicians

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 20th-century German non-fiction writers

- Conservatism in the United States

- Right-wing politics in the United States

- Old Right (United States)

- Physicians from Nuremberg

- Writers from Nuremberg

- Alumni of King's College London

- Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich alumni

- University of Erlangen-Nuremberg alumni

- University of Würzburg alumni

- American anti-communists

- American conspiracy theorists

- American psychiatrists

- German anti-communists

- German conspiracy theorists

- German psychiatrists

- German emigrants to the United States

- New York University faculty

- Physicians from New York City

- New York (state) Republicans

- Anti-crime activists

- Activists from New York City

- Comics controversies

- American textbook writers

- German textbook writers

- Anti-Marxism

- Anti-Masonry